Sources of Grain Size Variability: Sandy River, Oregon

For more information, this research is published in Geomorphology: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geomorph.2022.108447

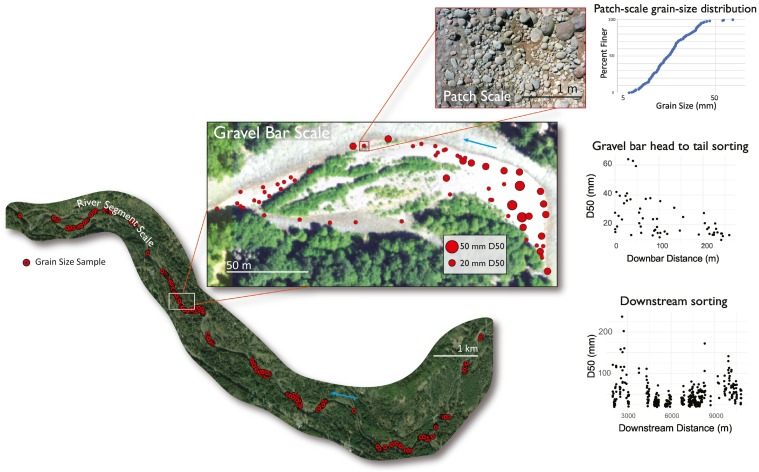

The upper Sandy River drains the flanks of Mt. Hood in northern Oregon, USA, and is characterized by its steep valley, large floods, and abundant sediment. The natural river dynamics are defined by its geomorphic history including glacier activity that carved the valley from volcanic bedrock, and volcanic emissions from Mt. Hood that have deposited masses of ash and rock fragments into the valley bottom. The Timberline Lahar 1700 years ago and the Old Maid Lahar 200 years ago introduced large volumes of sediment ranging from sand to boulders, forcing the Sandy River to readjust its form through incision, lateral migration, channel widening, and avulsions. These adjustments have organized sediment into gravel bars, which continue to develop during high flows today. The growth and erosion of these bars play a central role in driving channel adjustments and sediment transport rates. The upper Sandy River’s fluvial processes, such as channel migration, pose severe risks to nearby communities and have recently caused significant damage to infrastructure and homes.

A river’s sediment grain size patterns reflect flood magnitudes, hydraulic conditions, sediment supply, and aquatic habitat. Processes of fluvial grain size sorting operate at spatial scales ranging from the river’s entire longitudinal profile to small clusters of grains. At the scale of a few individual grains, size-dependent differences in inertia lead to pebble clusters as a single immobile clast encourages an upstream deposit of coarse bedload and a downstream deposit of fine material. Channel width scale bedforms, such as a gravel bar, exert topographic control over the flow structure leading to sediment sorting. At the scale of an entire stream or river, the exponential downstream decrease in grain size arises from size selective transport and abrasion processes.

A river’s sediment grain size patterns reflect flood magnitudes, hydraulic conditions, sediment supply, and aquatic habitat. Processes of fluvial grain size sorting operate at spatial scales ranging from the river’s entire longitudinal profile to small clusters of grains. At the scale of a few individual grains, size-dependent differences in inertia lead to pebble clusters as a single immobile clast encourages an upstream deposit of coarse bedload and a downstream deposit of fine material. Channel width scale bedforms, such as a gravel bar, exert topographic control over the flow structure leading to sediment sorting. At the scale of an entire stream or river, the exponential downstream decrease in grain size arises from size selective transport and abrasion processes.

The interdependencies among the patterns and processes of sediment sorting across these spatial scales are poorly understood despite the importance of the spatial distribution of sediment of different sizes for channel morphology, flow hydraulics, and sediment transport regimes.

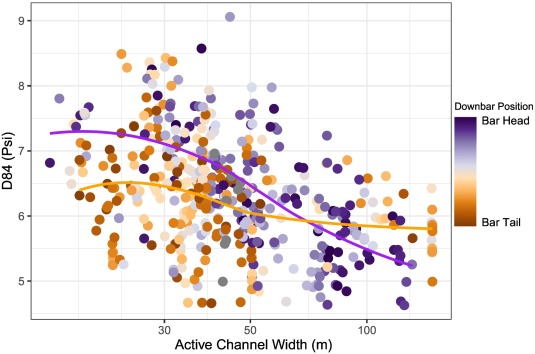

The inverse scaling relationship between active channel width and grain size (below) emerged as the most important source of grain size variability within the study area.  The mechanism remains an open question, but two hypotheses emerge from the results. The first potential explanation is that spatial differences in grainsize of external sediment sources such as riverbanks enabled channel widening to occur in specific locations. The second hypothesis is that channel widening occurred in particular locations because of differences in lateral channel confinement, which produced differences in flow hydraulics that caused sediment sorting.

The mechanism remains an open question, but two hypotheses emerge from the results. The first potential explanation is that spatial differences in grainsize of external sediment sources such as riverbanks enabled channel widening to occur in specific locations. The second hypothesis is that channel widening occurred in particular locations because of differences in lateral channel confinement, which produced differences in flow hydraulics that caused sediment sorting.

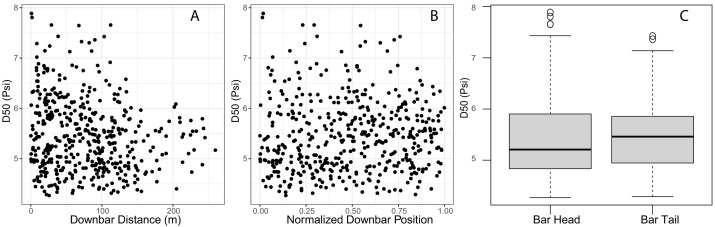

The grain size patterns within gravel bars (below) and their relationship to channel width (above) does provide insights into the role of flow hydraulics in sorting surface sediment. The active channel width is related to flow competence, which is the maximum transportable sediment grain size through the channel at a given discharge. Critically, the relationship between channel width and grain size is only apparent when considering bar-scale position as well. Overall, this research contributes to the growing capabilities to expand river surveys beyond traditional cross-sections and sporadic grain-size samples to gain a more complete understanding of the system.